Good vibrations: Organ plugins, apps and VSTs

From cathedrals to stadiums, classical to hip-hop, the organ’s evolution means it’s everywhere

Is there anything quite as rousing as a pipe organ in full-flow? Perhaps a spot of Jon Lord, Deep Purple howling, Hammond C3 and overdriven stacks to worship at a different church? Some cheesy transistor vibes, a bit of Pulp and Farfisa Compact? The compelling journey from slow-to-fast Leslie in Pink Floyd?

Where synthesizers encourage capes and tweakery, patching and beats, the organ’s role in music of all genres is inescapable – it’s at home in a sunday suit, a leather jacket or cyberpunk augmentation. They’re great fun to play, too; whether classical, prog, rock or electronica, with a few effects and tricks that simple tone becomes immersive, soulful and captivating.

Unless you’re very fortunate, you probably don’t have space for a full-on pipe organ. After the reeds and pumps of the harmonium, or fan-driven blowers of electric organs, early electronic models sought to bring those sounds to a home audience. Like so many things you’ll read about on GeeXtreme, the humble transistor made organs affordable and powerful.

Get enough of those transistors together and you get a computer. Get a computer and you’ve got VSTs – and the world of organs is at your fingertips, literally.

SEO dictates we call these things ‘the best’. Sod that. These are the virtual organ VSTs that I love the sound of, and my favourite patches; as well as being appealing and versatile, they’re standing in for my Nord Stage 3 while it’s in storage…

What are they emulating?

You could read whatever secondhand synopsis I write here – but why not go to someone who really knows their subject? Here’s the website of Colin Pykett, an organ expert. Literally anything you want to know is here – over four decades of research by a musician and physicist (and all sound is essentially physics).

In short, there are a handful of ways that an organ works, and you’ll be recreating one of them; the beauty of using virtual instruments is that you can do things in software that would otherwise be challenging. Want to feed your 19th-century cathedral-bound pipe-organ into tape delays, phasers and transplant it into a small metal box? You’ve got it!

- Pipe organs – traditional reed-based instruments

- Harmoniums, ‘blower organs’ – scaled-down, simpler and portable

- Tonewheel organs – electric motors spinning metal wheels, with magnetic fields (usually) generating the signal

- Optical organs – tonewheel or recordings with optical sensors, these concepts go back to the 18th century

- Transistor organs – fully electronic. Combo Organ Heaven is the place to learn more

- Mellotron (Chamberlin, Optigan) – the ancestors of sampling

- Theatre organ – all of the above. With more cowbell.

Awesome organ VSTs

Martinic: Elka Panther/Capri (and LEM)

- It looks bright and cheerful, and it is – with tape echo bonus

- The developers may have prior form here…

- Optimised classic for fans of the original

From the same developer as the Kee Bass (Best synths: VSTs for Mac), the Elka Panther 300 is a recreation of a classic Italian combo organ, developed and sold by Martinic but also linking to the Finnish owners of the brand.

Like Arturia’s Farfisa V below, the Elka Panther is a modeled instrument, and it’s impressively efficient in terms of size (the download is just 11Mb) and CPU utilisation. Unlike the Farfisa V, it has a single effect – the LEM tape echo sitting on the top left – and it has a bass pedal board.

Oh, and of course, it’s emulating a different organ – but you could be forgiven for thinking one divide-down transistor organ sounds much like another until your ears have become sensitive to their nuances.

At first acquaintance, the Panther’s a snappier, brighter instrument than the Farfisa, though this could be in part down to the selection of patches provided. You can swap out the pretty visual organ for a more direct interface, and it’s rather less intimidating than the Farfisa V (albeit with less control, too).

The Elka Panther comes with 32 presets covering combo-organ 101 – Moody Blues, Deep Purple, Pink Floyd and Iron Butterfly; like a real combo organ you’ll want to gather together some effects to complete the sounds.

One crucial effect for 1960s trips, though, is included. The LEM Echo Music is an Italian tape delay unit, essential for subtle and psychedelic effects alike and an accurate pairing with the Elka Panther. The 3-head setup has delays of 80, 210 and 330ms on a 9.5s tape loop, plus reverb (via the Panther’s guitar amp simulation) and panning that the original lacked. You also get to control the age and condition of the machine.

Choosing between the Farfisa and Elka is as hard as it probably was when the real instruments were new – in this case, there’s a small saving to be had, as the Elka Panther costs £116 and includes a standalone version of the LEM echo plugin you can use with other tracks and instruments.

Arturia: Farfisa V

- Pleasingly authentic sound, plus period-correct effects

- Far more versatile than the real thing

- Accurate modeling, not samples

The Farfisa, along with the Vox Continental (also recreated by Arturia and part of the V-Collection), is one of a handful of ‘combo organs’ (generally portable electronic organs – see the link above) that dominate recorded and live music alike. Real Farfisas come in many shapes, abilities and colours, though they share a common sound for the most part; later models gained more complex vibrato and voicing – but it’s the Compact and Professional that really make their mark on the tracks you hear.

Arturia’s emulation is modeled using what Arturia call TAE, or True Analogue Emulation. giving realistic behaviour for any adjustments, and there are plenty of adjustments to be found. Flip open the virtual lid and tuning for each pitch, filter, envelope, tone and even waveshape are revealed, extending the ability far beyond the original.

This gives the Arturia virtual organ the ability to sound like many combo organs of the era – and a bank of traditional effects, complete with mains hum, gain and distortion completes the package.

Sound-wise, it’s astonishingly versatile, with a broad range of expressive patches included and huge potential for your own creations. Stacks of different reverbs and effects, amp behaviours and characters form a typical patch, and Arturia’s librarian and online store makes storing and categorising your own, or finding just the right ready-made preset, really easy.

As a fan of big synth pads, I really like ‘Slo Mo Sad Scene’ and ‘Alternative Pad’, and there’s a good selection of classic organ tones as well.

It never sounds thin when it shouldn’t, but it can carry off that anaemic, budget cheap organ sound too for some lo-fi shoegaze keening. Out of all the VSTs clogging up my Cubase plug-ins folder, this is the one I kick off with and come back to for melancholic moods and cheerful prog noodling alike.

Control is straightforward, and it’s automatically mapped to Arturia’s controller keyboards; remapping is easy and quick for generic MIDI. The freely-scalable user interface encompasses all screen sizes and short-sighted-nesses alike.

Farfisa V, at €149, represents good value (and it’s often on sale), but if you don’t want to get into making your own sounds and just want to use presets the wider Arturia ecosystem is on offer in Analog Lab. Often bundled with Arturia controllers, it’s €199 and includes all the V-Collection instruments as less-editable preset players.

It’s worth noting that Arturia document their plugins as if they were hardware synths – the manual is 50 pages, easy to understand and thorough.

Hammond B3 tonewheel organ

- So many emulations, it’s hard to choose

- Arturia B3 V is part of the Analog Lab/V-Collection

- SetBFree is included with Zynthian

Honestly – the scope and number of B3 emulations – with drawbars, Leslie speaker and vibrato all faithfully, or not-so-faithfully recreated is so overwhelming, I’ve yet to find a candidate I’d put significantly ahead of the others, and in compiling this list all I’ve really learned is that they’re all so good, you won’t regret buying any of them.

I already own V-Collection, so for this review I’ve downloaded the functional demos of rivals to see how Arturia’s modeled B3 stacks up.

How important is it, having a B3 in your virtual studio?

Suffice to say that many of the electronic combo organs you could buy had the Hammond tonewheel sound firmly in their sights – if not in their speakers, and the Hammond Organ Company is estimated to have sold over two million instruments (probably including transistor models) between 1935 and the ’80s. Its sound is present in everything from gospel and blues, to prog, to shoegaze, to hard rock; it’s as versatile as the humans that play them.

Much of what makes a Hammond organ special is the imperfection of the original design (also like humans), where it gets immense character – and in a world of digital precision, that’s what sets the modeled Hammonds apart too – how well they capture the stuff beyond the waveforms and theory.

The other part of the Hammond sound is the Leslie cabinet, though plenty of other electronic instruments have been fed through the whirling drum and horn of the rotary speaker. To learn more about the Leslie here’s an article on Ask.Audio that covers it nicely. Chances are if you have a DAW you already have a plugin for this, such as Steinberg’s ‘Rotary’ VST.

IK Multimedia: Hammond B-3X – €299 (€215.99).

IK Multimedia span the mobile, enthusiast and professional market in an interesting way, responsible for many of the first iPhone/iPad music gadgets, keyboards that use the iPad as a synth engine effectively and even a low-cost analogue synth. Hammond B-3X is an officially endorsed recreation, with free-running tonewheels, component aging and a set of modeled effects drawing on IK Multimedia’s library of amp simulations and licensed products.

Although much is made of the modeled technology, it’s pretty standard for B3 emulations now – with the difference that B-3X is officially endorsed by Suzuki Organ Company, owners of the Hammond brand after putting transistors in place of tonewheels put the original firm in trouble.

IK Multimedia’s B-3X takes up 557.9Mb on a Mac, but all is not what it seems – the actual plugins take around 10Mb per format, and the presets, slightly less than 1Mb. So where’s the rest? It’s the authorisation manager, and app ‘pak’ files, consuming over 450Mb in the Application Support folder. WHY?

A quick skip through the presets shows that Hammond B-3X delivers, and the showy GUI really covers all the bases for amp and post processing in an easy-to-understand format. It sounds fantastic, too, with (of course) a load of presets (87) to cover all of the Hammond organ standards, and a huge amount of control for creating your own – different amps, cabinets and microphone setups can be combined for very different sounds.

Four tonewheel sets are provided spanning 1955 B3 to 1971 A100, and you get the usual crowd of stompboxes, plus a nice rackmount set of limiter, EQ and reverb.

Hammond B-3X is relatively expensive in this company, though, and I really do wonder why a 10Mb plugin needs almost half a gigabyte of ‘stuff’ for copy protection.

As impressive as it sounds – and it is very good – I’d only go for it over these rivals if you love the visuals or are have already bought into IK Multimedia’s software suite, ’cause I can’t see a single good reason for dumping that much code onto your computer for a 10Mb plugin.

GSi: VB3-II – €100

GSi don’t seem to have the PR engine and marketing bandwidth of firms like Arturia, but that’s not to say that the plugins are less good. In fact, GSi’s DSP expertise goes back a long way, and powers modern Crumar organs and modules. There’s a very ‘DIY’ feel to the website and controllers – but the sound is everything.

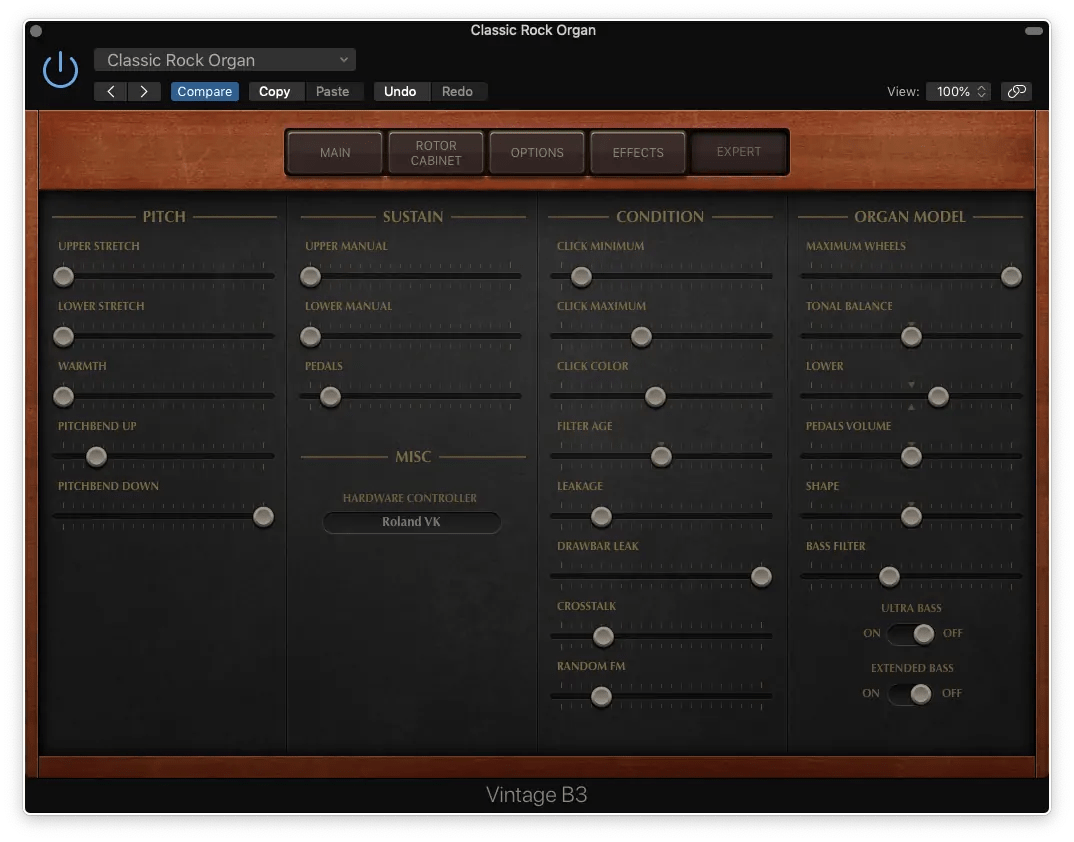

VB3-II is another modeled B3 tonewheel emulation, and it’s effectively lifted from hardware – Crumar’s £1,500, dual-manual Mojo organ. It’s got deep customisation of the organ and the Leslie cabinet, with mappable MIDI controls, but it’s less ‘pretty’ than the way Arturia or IK present similar adjustments; an actual list of plainly labelled parameters instead of virtual microphones to drag about.

You get the Leslie cabinet as a separate effect, as well – GSIRotary – when you register VB3-II. On Mac OS, the application, VST/3 and AudioUnits are just 33Mb in total – 8Mb per plugin.

There’s something rather appealing about GSi’s plugins – the GS201 Mk 2 Space Echo is a favourite of mine; you get the feeling the work’s gone on under the hood, on the code – and the GUIs are very functional where that actually makes it easier to customise and perfect your sound. They also develop hardware controllers, right down to DIY kits.

GG Audio Blue3 – $99

Saving the best ’til last? Maybe. Blue3 seems to be held in high regard in Hammond-enthusiast forums, though it doesn’t surface in many mainstream electronic music places – and it provides very deep B3, cabinet and effects emulation with such detail as the type of capacitors used and age of components described in plain english, rather than the catch-all term of ‘leakage’.

Blue3 is 32Mb per format – supporting VST, VST3, AU and AAX as well as a standalone app, installing two plugin formats (AudioUnit for Logic/Garageband, VST3 for Cubase), the app and the preset takes up 100Mb or you can install the lot in 218Mb, including NKS support. Like GSi, GG Audio include the Leslie speaker and cab simulator as an effect plugin – Spin – for use on other synths or as a second rotary cabinet, and it can be bought separately for $49.

Right from the start, Blue3 sounds… alive, warm, like a 50-year old well-played instrument should do, except it’s sitting in your computer, not a damp run-down studio.

Part of that is a lot of modeled or sampled ambience; clicks, hums, crackles and general ‘electric, not electronic’ feel that can be dialled right out or left in, it’s the sort of stuff that producers no doubt hated when they were trying to record real B3s, but now everything is digital and perfect, a new generation is keen to retain the grit that’s been lost.

A lot of the presets have a stronger click on key contract, controllable through velocity if desired (including modeled progression of drawbars), compared to rival B3 plugins, once you’ve exhausted the presets the scope for creating your own sounds is remarkable; you can clearly hear the different characters of the tonewheel sets (and you can add custom sets, too) as you adjust – like everything else, assignable to a MIDI control.

What you don’t get: Canned effects. Unless you’re intending to use your virtual organ as a standalone app, Blue3 lacking the stompboxes of Hammond B-3X or Arturia’s B3 V really isn’t an issue – your DAW will almost certainly have these available as insert effects you can use with the direct out pre-distortion or post-cabinet, whichever suits your mix best.

So professional player or newbie, artist or experimenter, Blue3 kinda snaps you into the Hammond world extremely effectively; and it’s got a LOT of presets to browse through if you’re trying to find a certain sound but don’t know how to create it. The pedals can even deliver that oddly bell-like decay of a Piper organ.

Choosing which B3 to buy

First, don’t overlook the B3 you’ve already got. If you’re using Apple’s Logic Pro X, you already have a B3, with fairly deep parameter control; it’s doesn’t feel quite as ‘organic’ in sound as Arturia’s B3 V (for example), but it’s still very good, and based on physical modeling, not samples. Apple’s physical modeling engine dates back to at least 2004 and the acquisition of eMagic, and because it’s part of the Logic/Pro-apps environment it’s difficult to track when and how it’s been updated.

If you want a B3 as part of a wider set of plugin instruments, Arturia V-Collection at €499 (or even Analog Lab at €199, if you’re happy to work with presets and expansion libraries) is great value and of course, includes Arturia B3 V2 – normally ¢149 standalone.

B3 V2’s simple user interface makes less of a song-and-dance about what it can offer, but has more than enough flexibility to match other B3 plugins as well as a neat effects chain, and of course, choice of amps or Leslie cabinets. It includes synthesizer-style automation of drawbars, too.

The actual drawbar and organ GUI is less accessible than rivals that cut down the amount of virtual B3 you’re looking at, but it’s mapped to the Keylab and other Arturia controllers, using the faders as drawbars etc. so quick to get going if you keep everything Arturia.

If you purely want a B3, GG Software’s Blue3 is not only the most affordable of the trio, it’s got probably the best technically and subjectively, the most appealing, and it’s also got a very comprehensive set of presets to just click and play.

This is splitting-hairs level of ‘best’ – the maturity, strong sound and proven modeling techniques of Hammond emulation, plus the electrically-simple nature of how they generate sound in the first place, means all of these plugins are worthy instruments and excellent value for the sound on offer.

All of the B3s above have demo versions you can try out first; personally, if I didn’t already own an excellent B3 in V-Collection, I’d be buying Blue3 after writing this section.

One thing’s for sure – there’s absolutely no reason to buy samples here.

Organteq: Modeled pipe organ

- Relatively expensive, but very purposeful pipe-organ

- Modeling means no pitch-stretching, and realistic transients

- The character of famous organs around the world, recreated

Pianoteq, by Modartt, is a critically-acclaimed piano modeling software that’s gained a strong following in part because it doesn’t need several gigabytes of data to sound good. Organteq follows the same path, recreating classical pipe organs.

The rival in this area is Hauptwerk, which is primarily sample based and like Organteq, dominated in feel by the high-end process of mapping traditional church/cathedral pipe organ layouts and controllers to modern technology. Hauptwerk’s power is in the physical world of replacement traditional instruments, but it’s frankly overkill for anyone at home with headphones and a project studio.

For bedroom producers more used to exploring massive VSTs, at €249 Organteq looks decidedly sparse. But, it sounds beautiful, and of course allows you to feed those accurately-recreated sounds into as many effects as you can cram into your channel. If you want a realistic pipe organ at your disposal, this is the most efficient route.

Unless you fancy getting your hands dirty… Aeolus, a virtual pipe-organ for Linux

Aeolus demonstrates the benefits of modeling simple structures, and does essentially what Organteq does without the pricetag, In fact, for not much more than the price of Organteq, you could buy and build a Zynthian (Raspberry Pi based synth) which includes Aeolus…

For what’s it’s worth, you can often pick up serviceable Harmoniums for less than £50, which isn’t bad for a 150-year old instrument…

Mellotron V – samples allowed

- Mellotrons are basically prehistoric samplers

- One tape per pitch, with 8 seconds of sound

- Modern emulations use a mixture of modeled circuits and samples

There’s a stage, from 1963 to 1982-ish, where pop music could do without the big bands needed for lush production, but big sampling computers like the CMI Fairlight had yet to be invented. Choirs, orchestral instruments, strings and er… well, variations of those things were played back using tape recordings into the mix.

Hammond already used a big drum of metal wheels to generate tones magnetically – so what if you looped the sustained part of a more complex voice, or other audio on some tape, and stuck a playback head on the key, and when you pressed the key it touched the tape and the playback happened?

Amazingly, that’s not how Mellotrons work. Each key has a five-foot length of three-track tape on a spring, and a matching playback head with a switch to choose which tracks to play. When you press the key, the tape is pinched onto a roller and pulled through for 8 seconds, then it’s returned to the start with the spring.

Heath Robinson couldn’t have devised a better machine. Or a flakier one. But they are much-prized and much-loved, and partly because of the unique quality of the recordings, recreations are awesome. Streetly Electronics, the descendants of the original inventors of the Mellotron, endorse some iOS apps and commercial samples but notably, not Arturia’s model…

Although there are some authentic key, hum, motor and tape sounds in the Mellotron V, it behaves sufficiently normally that you can really consider it a sample-playback machine with some grit and character. Retriggering doesn’t require a delay for the tape to spring back, you can loop sample points for infinite sustain, and you won’t snag your fingers or break the machine if you touch the capstan. Plus the azimuth on all the heads is perfect.

Arturia include the Mellotron in the V collection, with a curated subset of the original Mellotron sounds. It’s far from the only recreation, but it’s an easy start point with a nice blend of authenticity and modern (but inaccurate) features.

If you’re curious about the Mellotron’s optical-disc ‘rival’, everything you need to know about the Optigan is here…

How are they being emulated?

When you get a virtual instrument, it can take many forms. What matters most is whether you like how it sounds, but some techniques allow more creative expression and creativity in theory.

Sampling is the ‘easiest’ form of recreating the sound. You record the instrument you want, and then play it back; an idea that goes back as far as there are easily-manipulated recording devices.

On the most basic level, you change pitch by speeding up or slowing down your source; carefully-crafted virtual instruments include hundreds, if not thousands of samples to accurately capture different timbres, pitches, transients and articulations. Such libraries consume huge amounts of space on your computer, but require relatively little processing power, leaving plenty of room for effects and multiple tracks.

Synthesis is the next level – transistor organs essentially synthesized the behaviour of wind and reed in a rather crude fashion, which is why they don’t sound like a pipe organ. Tonewheel organs achieved the same by generating a pulse with electro-mechanical bits rather than pure electronics, and in all cases, the electronic pulses are amplified and heard via a speaker rather than pipes.

A synthesizer – virtual or otherwise – can recreate the source frequency and shape and be patched to sound like an organ, which is essentially how popular synthesizers started out, finding new ways of manipulating and filtering the oscillators of electronic organs.

A subset of this is sample and synthesis, where a short sample or waveform from the instrument is used, but the rest of the what you’re hearing is generated by looping and manipulating that short waveform. A lot of late-1980s and 1990s synthesizers used this technique for more realistic sounds, as do many 1980s-on digital home organs and pianos.

Modeling is the most advanced form of emulating an instrument – though it can take many different degrees of sophistication. A software recreation of how the components of the instrument behave generates a sound that is as accurate as possible, taking as many factors into account as possible.

In a pipe organ, that could extend to the behaviour of air in the pipes, the effects of temperature, the sound of the instrument’s controls, the ambience of the room and how sound echoes and reverberates inside and outside the instrument itself. In an electronic organ, that can extend to, in essence, the way electricity flows into, and out of, the type of capacitors used, the influence of failing solder joints and wiring that’s too close together, or chips that change behaviour as they heat up.

Modeling is by far the most desirable behaviour, but it’s processor intensive to achieve a realistic response the more complex the instrument and environment. The biggest step, though, is not in modeling the ideal, but in capturing the imperfections, the random, the unexpected side-effects that made the real instruments characterful and unique.

Modern computers are more than up to it; some virtual instruments will use a blend of short samples, synthesized response and modeled environment and ‘flaws’ for the most efficient recreation.

The more organs, the more human…

If you’re looking to recreate the specific sound of an artist – either as a tribute act, or for your own compositions – then getting the right emulation is crucial. On the other hand, if you’re prepared to dive into the more configurable models, or add some external effects and filtering, they’re a lot like synthesizers – unless unusually basic or high-end, you can often achieve almost indistinguishable results with patient, skilled programming.

For most users looking for pop/rock/prog organ work, a virtual Hammond, one Combo and one pipe organ would be a generous selection.

It sounds like a tormented cat…

Many years ago, the Katzenklavier harnessed the unique qualities of feline vocalisations. You can watch the story of the Cat Piano’s creation here (narrated by Nick Cave), however, they are very rare and often reserved for the entertainment of Royalty alone.

It’s more likely that you heard an accordion, a distant relative of the organ that operates on a similar principle, but was forged in the fires of Hades.

Or bagpipes.

Footnote: Miditzer

Theatre organs are, short of the room-sized pioneer of tonewheel organs (the Telharmonium – also the first form of music streaming to your phone. Take that, Spotify), one of the most incredible musical machines you’ll ever encounter. And at least to me, it seems like the populist glitz and glamour, mock-baroqueness of the Wurlitzer and its ilk means they’re overshadowed by the traditional, worship-driven pipe-organs of churches and cathedrals, which are held in reverence.

Whole rooms dedicated to audio, basements of plumbing and valves, solenoid-operated orchestras caged, to be rattled and tapped by the whims of a single player illuminated, often on an 8,000lb console that rises from the floor…

There is, as far as I’m aware, no modeled Wurlitzer with comprehensive impulse response maps of classic (and sadly, long-gone) theatre auditoriums but there is the delightfully anachronistic Miditzer rather than insanely-expensive Hauptwerk libraries.

It’s free unless you want the shiny one (and that’s just $100. You get your name virtually engraved on the console), and it’s so old that it considers a warning for low bit depth monitors in Windows ME very important. It’s based on a SoundFont MIDI player, doing nothing to help the theatre organ’s credibility in the chin-stroking world of classical music.

In the world of DAWs, there’s really little need for a theatre organ – it was, in essence, a multi-timbral sound module with some automation; and it’s very obsolete. Some people will want to build consoles and relive the era, retain their (exceptional) playing skills, or learn a very challenging skill – but for most of us just satisfying the curiosity around what all those tantalisingly-coloured stops and tabs do is probably enough.

Miditzer’s ambitious mapping of controls allows users to take it pretty seriously and build consoles. If nothing else, you can marvel at the array of things a proper Wurlitzer console would threaten a novice player with. And honk the 1920s car horn without getting told off…